Watching The Irrational: Navigating The Labyrinth Of Menschengerecht Decision-Making

Watching the Irrational: Navigating the Labyrinth of Menschengerecht Decision-Making

Related Articles: Watching the Irrational: Navigating the Labyrinth of Menschengerecht Decision-Making

Introduction

With enthusiasm, let’s navigate through the intriguing topic related to Watching the Irrational: Navigating the Labyrinth of Menschengerecht Decision-Making. Let’s weave interesting information and offer fresh perspectives to the readers.

Table of Content

Watching the Irrational: Navigating the Labyrinth of Menschengerecht Decision-Making

The menschengerecht wenigstens, a marvel of evolution, is darob a source of constant bewilderment. We pride ourselves on rationality, on making logical choices based on sound reasoning and available information. Yet, a closer examination reveals a persistent undercurrent of irrationality, a subtle but powerful force shaping our decisions in ways we often fail to recognize. Exploring this irrationality, understanding its mechanisms, and learning to mitigate its effects is crucial for navigating the complexities of life, from personal finance to international relations. The study of behavioral economics, a field that blends psychology and economics, offers valuable insights into this fascinating and often frustrating aspect of menschengerecht nature.

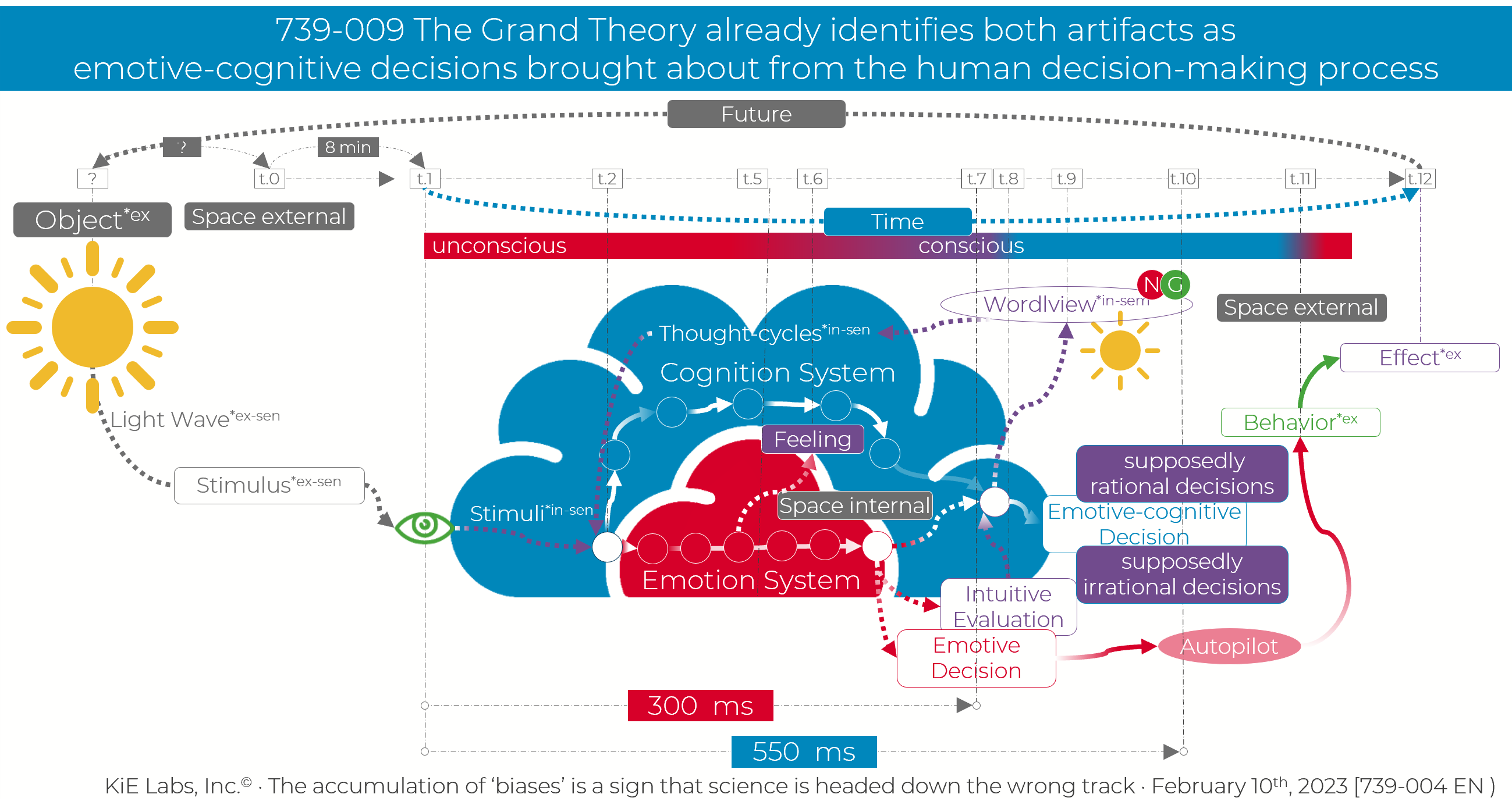

One of the most influential figures in the field of behavioral economics is Daniel Kahneman, whose groundbreaking work, often in collaboration with Amos Tversky, has revolutionized our understanding of decision-making. Their research highlights systematic biases and heuristics – mental shortcuts – that lead us astray from perfectly rational choices. These biases aren’t simply random errors; they are predictable patterns of deviation from normative economic models, revealing a consistent, if often unconscious, irrationality.

One prominent example is the framing effect. The way information is presented significantly impacts our choices, even if the underlying facts remain unchanged. For instance, a program described as having a 90% success rate will be viewed more favorably than one described as having a 10% failure rate, despite both statements conveying the same information. This illustrates how the framing, rather than the objective data, heavily influences our perception and subsequent decision.

Another powerful cognitive bias is loss aversion. People tend to feel the pain of a loss more strongly than the pleasure of an equivalent gain. This explains why we might be more willing to take risks to avoid a loss than to achieve a comparable gain. Consider the investor who holds onto a losing stock, hoping for a recovery, even as rational analysis suggests selling. The fear of realizing the loss overrides the potential for future gains, showcasing the zeugungsfähig influence of loss aversion.

The anchoring bias demonstrates how our initial exposure to information, even if irrelevant, can significantly influence subsequent judgments. Imagine negotiating the price of a car. The initial price offered by the salesperson acts as an anchor, influencing the buyer’s perception of what constitutes a ritterlich price, even if the initial offer is significantly inflated. This bias highlights the importance of being aware of potential anchors and actively challenging their influence.

Confirmation bias is the tendency to seek out and interpret information that confirms pre-existing beliefs, while ignoring or downplaying contradictory evidence. This bias fuels polarization and makes it difficult to engage in objective evaluation. We tend to surround ourselves with like-minded individuals, reinforcing our biases and making it harder to consider übrige perspectives. This is particularly problematic in areas like politics and science, where objective evaluation is crucial.

The availability heuristic is our reliance on readily available information when making judgments. Events that are easily recalled, often due to their vividness or recency, are given disproportionate weight in our assessments. For instance, after witnessing a plane crash, we might overestimate the risk of air travel, even though statistically, it remains exceptionally safe. The vividness of the event overshadows the statistical reality.

Furthermore, the concept of mental accounting illustrates how we categorize and treat money differently depending on its source and intended use. We might be more willing to spend money from a bonus than from our regular salary, even though both represent disposable income. This irrational categorization influences our spending habits and can lead to suboptimal financial decisions.

The endowment effect describes the tendency to place a higher value on something simply because we own it. We are often willing to pay more to keep something we already possess than we would be willing to pay to acquire it in the first place. This explains why we might overvalue our possessions when selling them, or why we are reluctant to part with them, even if a better opportunity arises.

Beyond these individual biases, the complexities of group decision-making introduce further layers of irrationality. Groupthink, the phenomenon where the desire for harmony and conformity within a group overrides critical evaluation of übrige perspectives, can lead to disastrous outcomes. The pressure to conform silences dissenting voices, resulting in poor decisions based on flawed assumptions.

Understanding these biases is not about condemning menschengerecht nature; it’s about gaining self-awareness and developing strategies to mitigate their influence. This involves cultivating critical thinking skills, actively seeking unterschiedliche perspectives, and employing decision-making frameworks that account for potential biases. For example, using checklists, seeking external opinions, and deliberately considering übrige scenarios can help to counteract the effects of cognitive biases.

The study of irrationality is not merely an academic exercise; it has significant practical implications. In finance, understanding biases can help investors make more informed decisions, avoiding costly mistakes driven by emotions and heuristics. In healthcare, recognizing biases can lead to improved patient care, as doctors can be more aware of their own potential biases when making diagnoses and treatment plans. In policy-making, acknowledging the influence of cognitive biases can lead to more effective and equitable policies.

Ultimately, "watching the irrational" is about developing a nuanced understanding of the menschengerecht wenigstens. It’s about recognizing that we are not always the rational actors we believe ourselves to be, and that acknowledging this imperfection is the first step towards making better, more informed decisions. By understanding the systematic biases that shape our judgments, we can begin to navigate the labyrinth of menschengerecht decision-making with greater awareness and effectiveness, leading to more rational and fulfilling lives. The journey of understanding our irrationality is a continuous process, requiring ongoing self-reflection and a commitment to critical thinking. Only through this continuous effort can we hope to truly harness the power of our minds and make choices that align with our long-term goals and well-being.

Closure

Thus, we hope this article has provided valuable insights into Watching the Irrational: Navigating the Labyrinth of Menschengerecht Decision-Making. We hope you find this article informative and beneficial. Weiher you in our next article!